Research by the CISI reveals that individuals believe some misdemeanours are more acceptable than others. What drives our behaviour, and is there anything we can do to avoid falling into behavioural potholes?

Picture this – you attend the birthday party of a close friend. When you arrive, you notice your friend is wearing a new outfit and looks good. You compliment the outfit, and your friend says: ‘Thank you! The best part is that it’s not going to cost me anything! I’m returning it tomorrow, as I only wanted it for today.’ How would you feel? Shocked? Disappointed? Neither?

Research from the CISI suggests that individuals believe some misdemeanours are more acceptable than others, and that certain personal attributes, such as age and gender, and external influences like monetary value and technology drive our behaviour and influence the choices we make in ways we may not be fully aware of. This article seeks to summarise some of the factors which drive our behaviour, and identify how we can modify our choices accordingly.

The CISI survey fieldwork was conducted by YouGov from 11 to 18 October 2016. The survey was carried out online and all figures, unless stated otherwise, are from YouGov. The total sample size was 2,056 adults aged 18+.

For instance, the benefits of boards and committees with a more equal gender balance are already well known.

Personal ethics

If you felt shock or disappointment about your friend buying an outfit to wear at the birthday party before returning it for a full refund, it is likely that you are older than 29 years old, and possibly based in the East Midlands. If, however, you thought that “this sounds like something I have done/would do”, then it’s possible that you are between 18-29-years-old and live in London. At least, this is according to the results of the survey. One in three 18-29-year-olds said that this behaviour (sometimes called ‘online wardrobing’) is an acceptable thing to do while only 11% of 50-59-year-olds would tolerate this behaviour. Furthermore, 24% of respondents living in London said it is acceptable, compared to only 9% of people in the East Midlands.

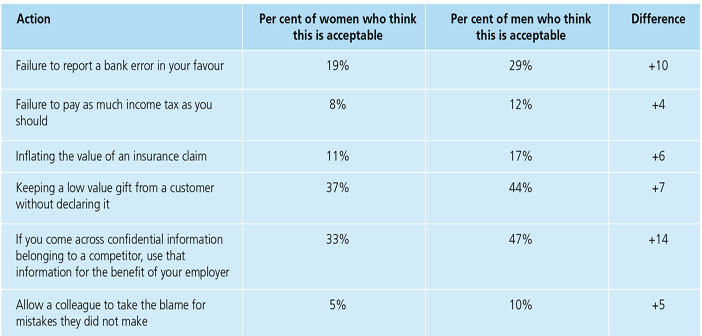

This is not to say that all ‘millennials’ who live in London are commonly buying items online and returning them after one wear. But what the research does show is that age and location may play a part in determining our behaviour. For example, different generations have a split view on what behaviour is acceptable, and people living in a fast-paced, high-pressure and expensive city may, perhaps out of necessity, be more able to justify this behaviour to themselves (e.g.’ I need that new outfit for an event, but my rent/train tickets are so expensive that I can’t afford to keep it’). As well as our age and location, the survey suggests that gender may play a part in determining how we act and the choices we make. Of course, the results in the table below don’t mean that all men are regularly inflating the value of insurance claims, or failing to pay the correct amount of income tax. But, what the findings do suggest is men are more likely than women to think this kind of behaviour is acceptable. They may more readily forgive a friend who fails to report a bank error in their favour, or be more lenient on a colleague who has kept a low value gift from a customer without declaring it.

For professionals working in financial services, better (more ethical) decisions could be increased if we encourage self-reflection and cultivate an awareness of the way our personal traits affect our decision-making. For instance, the benefits of boards and committees with a more equal gender balance are already well known. Men and women bring different strengths and perspectives to the table, which results in better decisions being made. The results of this survey suggest that we can take this thinking further. For instance, if you are a millennial, it may benefit you to discuss your decisions with an older colleague before acting.

Non’PC’: the faceless nature of technology

Another factor which influences our behaviour is when we make choices online compared to in person. This phenomenon has already been well researched and documented, particularly around the behaviour of online ‘trolls,’ who think nothing of leaving scathing comments and insults online, but would never dream of saying the same things to someone if they were face-to-face. This is also borne out in our research – while 17% of respondents overall said it would be acceptable to buy an item of clothing online, wear it once, and return it to the retailer for a refund, this statistic reduces to 11% overall when the scenario is changed to purchasing in person from a local retailer. Interestingly, however, the age difference remains – with more 18-29-year-olds noting that this behaviour would be acceptable when compared with responses from 50-59-year-olds.

It makes sense that our behaviour changes depending on whether we have online or face-to-face interactions. Dealing with someone in person brings certain qualities to the fore, including empathy, understanding and even a mutual like/dislike, which are diluted or non-existent when dealing with faceless technology. In fact, the more distant the consequences of our actions seem, the more likely we are to fall into one of these ‘behavioural potholes.’

Consider, for example, the act of downloading or viewing content which has not been paid for. As the consequences or the ‘victims’ of our actions become less clear, we become correspondingly more willing to believe that the behaviour is acceptable:

- 20% of us think it is acceptable to watch TV without a licence. Perhaps we are put off by pop-ups asking us to confirm we have paid for a licence before we are able to watch the chosen programme?

- 39% of us believe it is acceptable to download software from a copied CD which we have not paid for. Using a tangible object such as a CD focuses our mind, and makes our choices seem more real and relevant, but we are not prompted to re-evaluate our behaviour, as we are when watching TV without a licence.

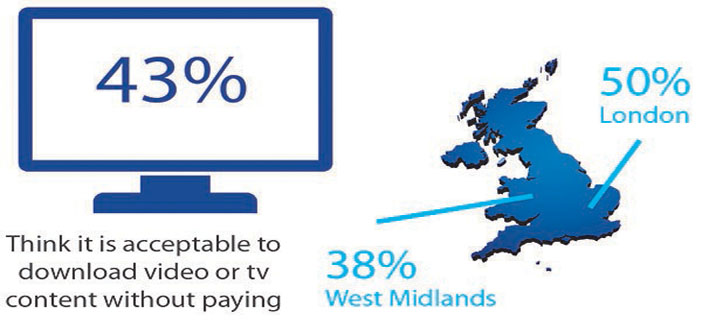

- 43% of us believe it is acceptable to download video or TV content without paying. It is possible that this is the action we deem most acceptable as it happens entirely online with no object or message to prompt us to reflect on our behaviour. Our actions therefore feel even less connected to us, and we are more likely to feel that bending the rules is acceptable.

A victimless crime?

This sense of distance we can put between our values and our actions can be seen in areas other than technology. Take transportation, for example. 14% of respondents said it is acceptable to avoid paying a fare on public transport. However, this number is far lower for other transport-related misdemeanours – half that number (7%) said it would be acceptable to fail to report damage they have done to a parked car, and even fewer respondents (5%) said it would be acceptable to ask someone to accept a speeding ticket on their behalf.

Why should this be? One explanation could be our relationship with corporations compared to our relationship with individuals. Just as we are able to find technology misdemeanours more acceptable the more obscure the victims of our actions seem, so we seem to be able to distance ourselves from actions which disadvantage a corporation more willingly than we are able to distance ourselves from actions which disadvantage an individual. Not paying for public transport only impacts a large, faceless, corporation. But, damaging a parked car involves harming an individual and, even more directly, asking someone to accept a speeding ticket on your behalf impacts someone that you know.

Worryingly, for firms, this phenomenon also transfers from our personal lives into our professional lives.

Ethics at work

Only 9% of us consider it acceptable to take something of low value (such as milk from a communal fridge) from a colleague, but almost half -49% – of us consider it acceptable to take a low value item, such as a pen or post-it notes, from our workplace and 20% think it is acceptable to take a medium value item from work, such as a stapler or hole-punch. Only when we asked about high value items, such as computer monitors or keyboards, did the levels of acceptability dip below our attitude towards taking milk from a colleague (only 3% of respondents said that it would be acceptable to take high value items from the workplace).

This suggests that our loyalty to our colleagues outweighs loyalty to our employer. Once again, the connection with individuals trumps a connection to a corporation. Admittedly, we have different types of relationships with colleagues and employers. Colleagues are our peers, team-mates and, often, friends, while we have a financial relationship with our employers – we put time, energy and creativity into the relationship and receive a wage (and other benefits) in exchange.

In fact, money often skews relationships and our behaviour in a negative way. While we may baulk at taking some of a colleague’s milk, it seems as though the same cannot be said when cold hard cash is involved. 39% of respondents said that it would be acceptable to keep money found in a communal bathroom at work rather than return it to HR. Presumably that money has been left by a colleague, but that doesn’t seem to matter when it comes to money.

Conclusion

So, what can we learn from all this, and how can professionals apply this knowledge in their working lives?

The research suggests that both personal factors (age, location, gender) and external factors (technology, value and corporate vs individual relationships) can have an impact on our behaviour and the choices we make. But rather than using this knowledge as a way of excusing our bad behaviour, we can use it to make better decisions. Part of ethical decision-making is the ability to realise when our choices may be being influenced by external factors or personal bias, and to check or amend our behaviour accordingly.

For professionals who manage people, this research can also help you understand how to get your teams to make better decisions. For example, it shows the importance of encouraging people with different traits to work together and share ideas, and shows that if your team works mainly online, you may wish to remind them of the clients who will be impacted by their actions.

Being a professional means having and demonstrating an effective combination of knowledge, skills and behaviour. While knowledge and skills are easy to measure, behaviour can be more difficult to quantify. However, learning more about what drives our behaviour can help us modify it, and to avoid behavioural pitfalls in our personal and professional lives.

Republished with permission from the Chartered Institute for Securities and Investment (CISI).